Bio

Michelle Daniel Jones, ABD, is a fourth-year doctoral student in American Studies at New York University. Michelle's dissertation focuses on creative liberation strategies of incarcerated people. As an organizer, collaborator, and subject matter expert, she creates opportunities to speak truth to power and serves in the development and operation of task forces and initiatives to reduce harm and end mass incarceration. She has joined Second Chance Educational Alliance as a Senior Research Consultant, the Survivor's Justice Project, and serves on the boards of Worth Rises and Correctional Association of New York and advisory boards of the Jamii Sisterhood, The Education Trust, A Touch of Light, Urban Institute, and ITHAKA's Higher Ed in Prison Project.

She is board president of Constructing Our Future, a housing organization created by incarcerated women in Indiana. Michelle's fellowships include Beyond the Bars, Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History at Harvard University, Ford Foundation Bearing Witness with Art for Justice, SOZE Right of Return, Code for America, and Mural Arts Rendering Justice. Michelle is publishing with The New Press history of Indiana's carceral institutions for women with incarcerated and formerly incarcerated colleagues. As an artist, Michelle finds ways to funnel her research into theater, dance, and photography. Her co-authored play, "The Duchess of Stringtown," was produced in 2017 in Indianapolis and New York. Her artist installation about weaponized stigma, "Point of Triangulation," ran in New York 2019 and 2020 and, with new participants, 2020 to 2021 in Philadelphia with a public mural in October 2021.

"So, there are ways to deal with people who have done harm that don't encompass the intersectionality discrimination of race, sex, gender, and criminality. But in the United States, we don't practice that. Race is critical to the way in which we punish. And criminalization, long perpetual criminalization is key to how formerly incarcerated people remain in as Michelle Alexander said, ‘a perpetual outcast status.’"

Michelle Daniel Jones

Interview

I am a doctoral student at NYU and I am a changemaker.

In my studies in the American Studies program, I've had the opportunity to really study the carceral state and a lot of the texts that I have read obviously do not paint a glowing story. A lot of them do give you moments of resistance in which incarcerated people have organized, or families of incarcerated people have organized, you know, stories of jails and prisons closing, cases won, etc., etc. But I'm more interested in the internal processes that people go through emotionally, psychically, to handle the carceral regimes that impede their freedom.

For the formerly enslaved, of course, that was the Black Codes. The institution of Jim Crow laws and of course, just a flagrantly abusive criminal justice system that swept hundreds of thousands of Black people off the street who were freed so that they could labor in convict leasing camps. But they also had practices of Liberation.

What traditional history does is skip the moment of redemption in the history and jump all the way to the 1920s as if the Harlem Renaissance sprung from, I don't know... nothing. And I want to know about those people who were in the deepest transition from slavery to former enslaved status and how did they practice liberation? And I want to compare that to formerly incarcerated people today who are also under a carceral regime of collateral consequences of criminal convictions, right?

So, there are forty-eight thousand laws on the books across the country that bar or hinder access to opportunity for formerly incarcerated people, and each city has around a thousand or more. So how are formerly incarcerated people today achieving any kind of degree of freedom in this state of unfreedom? If they are have they had opportunity to learn from any of the lessons of the past?

I'm interested in those liberatory practices because that is not something investigated in our current carcel state literature. Of course, the American Studies field has a subfield called Critical Prison Studies but currently, there isn't any scholarship that encapsulates that.

ROOTS OF MY WORK

What brought me to this work? First of all, I'm directly impacted. I was incarcerated in the state of Indiana for twenty years and some change. But truly, more than that, the cumulative effects of the carceral state on the quality of life for families, children of incarcerated parents, and those directly impacted themselves, simply can't go unexamined anymore. It's too prevalent, it touches too many lives, everyone is less than six degrees away from it, and some of us in multiple ways. It is something that must be examined. It's something that must be challenged, but if we don't understand how it's constructed, we won't dismantle it appropriately. We will tweak, we will tweeze, we will pick at it, we will try to call it by another name.

We are woefully damaged by the lack of our understanding of how these systems came to be. For example, people look at the development of Black Lives Matter and, in their current experience, they think it springs out of nothingness or just a current contemporary experience. But if you look back, if you look back the roots of Black Lives Matter, are as old as slavery itself. A lot of people who do not understand those origin stories, will always look at the present moment uninformed.

GUIDING WORD

So, I'm a fellow from a group called Beyond The Bars, and one of the things that we did was an extensive study on race, criminalization, and the carceral state. We had to come up with one word that encapsulated what we wanted our work to be about. And [laugh] I struggled right, because I'm an abolitionist, so I wanted to dismantle, dismantle, dismantle but it didn't encapsulate the reimagining, because if you just destroy something, then what's in its place, right? So I came up with this phrase, I'm a 'trans-dismantalist.' I want to transform as I dismantle and that is… I want transformation for us while we dismantle and reimagine how we deal with people who harm people (and it's not a word)!

LEARNINGS

I have learned that the carceral state as we know it today cannot be thought-through, thought-about, or considered without understanding its intersectionality, right?

The carceral state is a place that punishes while it disciplines, but it punishes across race, sex, gender, and criminality. A lot of people look at the individual who's on TV, and they deal with the individual, and they talk about the individual, or they'll focus on an individual case, and they don't pull back and look at main structures that are operating in the system. Whether day or night, left or right, there are fundamental structures of race and criminalization that are fundamental in how we deal with people who have done harm.

So, there are ways to deal with people who have done harm that don't encompass the intersectionality discrimination of race, sex, gender, and criminality. But in the United States, we don't practice that. Race is critical to the way in which we punish. And criminalization, long perpetual criminalization is key to how formerly incarcerated people remain in as Michelle Alexander said, ‘a perpetual outcast status.’

The rhetoric, the axiom that 'you do the crime, you do the time' and that somehow your debt to society is paid as a result of that, is a prevailing myth. It's a myth. It is a complete myth. With 48,000 laws on the books that block or hinder access to opportunity for formerly incarcerated people, the legal arm of civil debt, and then the social consequences of criminal convictions, that social death. For example, the woman who couldn't get a dog from a rescue shelter because she had to check a box. That's social; it's not a law anywhere, but the social is the overarching umbrella that the legal is under. Most people will have an open conversation about the legal, but most people don't want to talk about the social because that gets where they live. That gets to how they enact discrimination at the grocery store, at the dog shelter, at the PTA meeting. I know people who couldn't coach their kids Little League because they had a criminal record 5, 10, 15 years ago. We cannot change the system until we acknowledge the ways in which we weaponize stigma, and how we weaponize social consequences of criminal convictions with one another. We won't get there.

SUCCESSES

Successes. First of all, there is a cadre of amazing women across the country who are organizing with one another taking the issues that have directly impacted formerly incarcerated women to the state legislatures. They are lobbying but I don't like the word lobbying, so we're calling it educating. We are forming partnerships and relationships on the ground with state legislators that would have been unheard of before. In the state of Indiana, we passed a bill,

House bill 1432, which we're very proud of. What it does is it eliminates the mandatory termination of parental rights of men and women who have children in the system fifteen or twenty-two months. It is a Clinton-era throwback on tough-on-crime, punitive positions that got passed in the state of Indiana and it was devastating to families, women and men who were going to prison for short-term incarcerations, were permanently losing the custodial rights of their children. This bill stopped that.

So, things are happening really, really good things are happening, and we're starting to have more collaboration between academia, activists, and directly impacted people. Again these were conversations that weren't being had before. The academic had a tendency to go into the marginalized area, conduct their research, return to their hallowed offices at their universities, type up their wonderful publications and leave, and never return to that community in which they have extracted stories and information from.

That's starting to change. We're starting to put on the forefront that you cannot be extractive, and it be okay anymore. Participatory Action Research [the PAR] is also growing in prevalence where you're bringing the people who are the subject of your studies, into the research process so that they are collaborators with you, with the academic. And so, these kinds of things signal a shift, where we begin to epistemically privilege the experience of the directly impacted and their families.

It's a shift from the past, and of course, we're still dealing with places where we go where we still experience epistemic violence. In other words, we experience the lack of the right to be knowers and someone else dictates what a re-entry program should look like. Someone else dictates where you should be going for services. Someone else dictates what your life after prison should look like.

Those conversations, those realities we're still challenged with, but there's a growing wave of people who are waking up to the value of having directly impacted people and their families at the table, at the public policy table, at the community level table, and that's encouraging for me.

THE ARTIST’S ROLE

We have to acknowledge the role of the artists in this work as well. I'm an artist, I'm a playwright, and I have an amazing project, a photography project, that I'm working on and bringing all of that together through the lens of the arts. The beautiful thing about the arts is that we're able to approach the concept, approach the challenges from a particular lens that can illuminate the whole thing, the whole structure for others who may not want to sit down and read Golden Gulag or The New Jim Crow or they don't want to watch 13th, or see When They See Us, they don't want to do that. But maybe they'll go to an art exhibit where someone is challenging the stigma of the formerly incarcerated people.

FOUNDATIONAL BOOK

The one that was a game-changer for me was Becoming Miss Burton by Susan Burton. Susan Burton is the founder of A New Way of Life in Los Angeles, and she has five transitional homes for women, but her story about how she came from sexual violence, through multiple levels of incarceration, to drug addiction, through the loss of her son, to the fragmentation of her family, the disintegration of her family, and somehow, got to a point was like ‘I am going to be the creator of my own solution’.

I was sitting in a cell. I had just signed a contract to go to New York University, and it suddenly was very real that a lot was expected of me, and that I had chosen to bet on myself in a big way. At that same moment, I'll never forget it, Kendra Hovey, who runs an amazing program in Ohio, was in Indianapolis at the facility and gave me that book. I realized after I read that book, that if she can come from all that she's come after, come from and been through; if she can come from all of that and then bet on herself and go out and create this amazing opportunity for other women, get what she needed to be stable and then go to do what she needed to do for other people, it was like, “Okay, Michelle, get over yourself, you've got this”. But I had that moment like, can I do it? And reading Susan Burton's book really told me that, “Your circumstances are dire, they are difficult, you've come through a lot, but look at Susan. Her circumstances were difficult and trying, and she's come through a lot, and look what she's doing.”

And then, of course, when I got out, I met other amazing women of color doing very similar things and amazing African American women scholars who didn't have the perfect, perfect, perfect background. And I was like, okay. It took me about a year but I've slowly gotten to the place where I feel like I belong here.

It's a game-changer. I've read other memoirs but what she does is she situates her story inside the structural issues in her city, state, country at the time, which is a critical appointment for a memoir. Because most people just tell their story, and they don't have the deep reflection of the structures that helped create the box that they walked in. You know there is a box, the structures of society in the neighborhood, in the home, in the marriage, it creates these layers that when crime happens, it's not causal, right? When crime happens, it's not causal. When it happens, it is a part of a rippling effect that gets all the way out to structure and frameworks. Her book helped me know that in a real-life scenario.

FINDING ONE’S VOICE

I was a very rambunctious, active child singing and dancing and moving and not sitting still, so I've always had presence and energy, and enthusiasm. When I realized that what I had to say mattered in a big way, I would say, I was inside, and I had formed a liturgical praise dance group in the facility called LIFTED. Suddenly, I had a lot of young people who were incarcerated in their 20s and who I was responsible for teaching a curriculum and teaching dance and being a mentor for, and I realized then that I had a voice. That I had a voice and also a responsibility. It helped direct how I moved about the facility and, as I developed other programs and moved on and, you know, LIFTED is still in existence right now in its 21st year. I'm proud of having created something that is serving a prison population, and I'm no longer there.

When I began researching and writing the first 15 years of the Indiana women's prison history, and we started writing up our findings and having the audacity to apply at conferences and videoconference into these academic conferences from the prison, I didn't falter because I had already established that I had a right to speak and be and I took that very authoritatively into the history project.

We are rewriting the history of women's carceral institutions in the state of Indiana. That includes homes like the Home for Friendless Women that was run by Quakers, the Magdalene Laundries that was run by Catholic nuns, the Madison Correctional Hospital, a facility that was a prison after being an insane asylum, and of course, the Indiana Women's Prison, which is my primary focus. It was the first separate public institution for women in the country and it opened in 1873.

The facility (now the Indiana Women's Prison) at that time was called The Indiana Reformatory Institution for Women and Girls and it was opened primarily to remove women from the co-ed men's facility in Jeffersonville. Those women were being raped. Guards would be charged $10 a month by the warden to have free rein with the women there. There were babies in that department that had been born as a result of being incarcerated and the goal was to remove those women, some of them charged with prostitution, to a separate facility. So that's why it was created, but one of the things that we found is that not a single woman was incarcerated for sex offense in the first quarter of a century. We were like, wait a minute, if this was created for women who were convicted of sex offenses, where were they? And that actually led to the uncovering of an old Indiana history about the

Indiana Magdalene laundries that is not a part of our standard history texts. No Indiana historian has written about it so we were able to excavate that research, and now we have an entire section that just kind of deals with the findings that we have found as a result of doing this deep archival research. In addition to that, we learned that the president of the AMA, American Medical Association, Dr. Theophilus Parvin (who is related to the father of eugenics in the city, Amos Butler), examined, experimented, conducted surgeries—clitorectomies and ovariectomies—on women and girls who were incarcerated in this facility. That history was not a part of the traditional canon of Indiana history of carceral institutions so we have excavated the role of eugenics and medicalization in Indiana history for women.

CHANGING THE NARRATIVE

The role of women's prison reform movements in the continuation of a crime and punishment regime in the reformatories in which they created was not an inevitable choice. It wasn't inevitable that they turned to solitary confinement. It wasn't inevitable that they locked women in closets. It wasn't inevitable that some of the Magdalena Laundries have cesspools of dead babies, it's not, and it wasn't inevitable. It was a choice. When women prison reformers had the opportunity to create a different way to deal with women who had committed harm in society, they could have reimagined something beyond replicating the toxicity of men's facilities across the country.

A lot of people would argue that it was inevitable but in my research, I found that it was a choice. It was a choice that set us back in terms of reimagining how people who do harm to each other can be redeemed in society. After they've done whatever time that's been allocated or after they've sought out another way, other ways, other than incarceration, to help someone. Our women prison reformers decided that a woman needed to be incarcerated to be helped. And that meant women, that meant kids, that meant teenagers, that meant us all. And as women, it set us further back to reimagine a society that has a different response, a totally different response, when people fall short.

And that's where we have to get today. We over incarcerate so that people who are actually truly mentally and emotionally broken can't even receive help in most facilities because there isn't any contractual money with the private corporations that provide services in prison to help them. There are simply too many people in the system.

So, the people who could be redeemed, if we focused on them, the people who are really, truly broken and are really, truly harming others from a place of true, true brokenness, if we can't ever, I feel really passionately that if we don't decarcerate, if we don't abolish, if we don't stop overusing prisons, we'll end up producing more brokenness that will continue the system as it is. And it will actually get more deteriorated and sick and cesspool-ish. I've simply watched the difference of one facility in a 20-year incarceration that did not have privatized services, and what it turned into once it did have them, and then what it turned into when it got crowded, and then what it turned into when it got overcrowded, and nothing fundamentally changed about who was incarcerated, how we incarcerate, why we incarcerate and that facility is a cesspool today.

Breaking that down, dismantling that, is going to require all of us to be a part of the conversation. And, you know, we get a choice here. We don't have to continue with things the way they've always been simply because that's the way things have always been.

Related Links

IG:

@michelle__thetruth

Twitter:

@COF_Michelle

LinkedIn:

https://www.linkedin.com/in/michelle-daniel-jones/

Website:

michelledanieljones.com

Shawnda Chapman-Brown

Shawnda Chapman-Brown Rebecca Epstein

Rebecca Epstein Donna Hylton

Donna Hylton Drew Dixon

Drew Dixon Elisha Fernandes Simpson

Elisha Fernandes Simpson Nina Bernstein

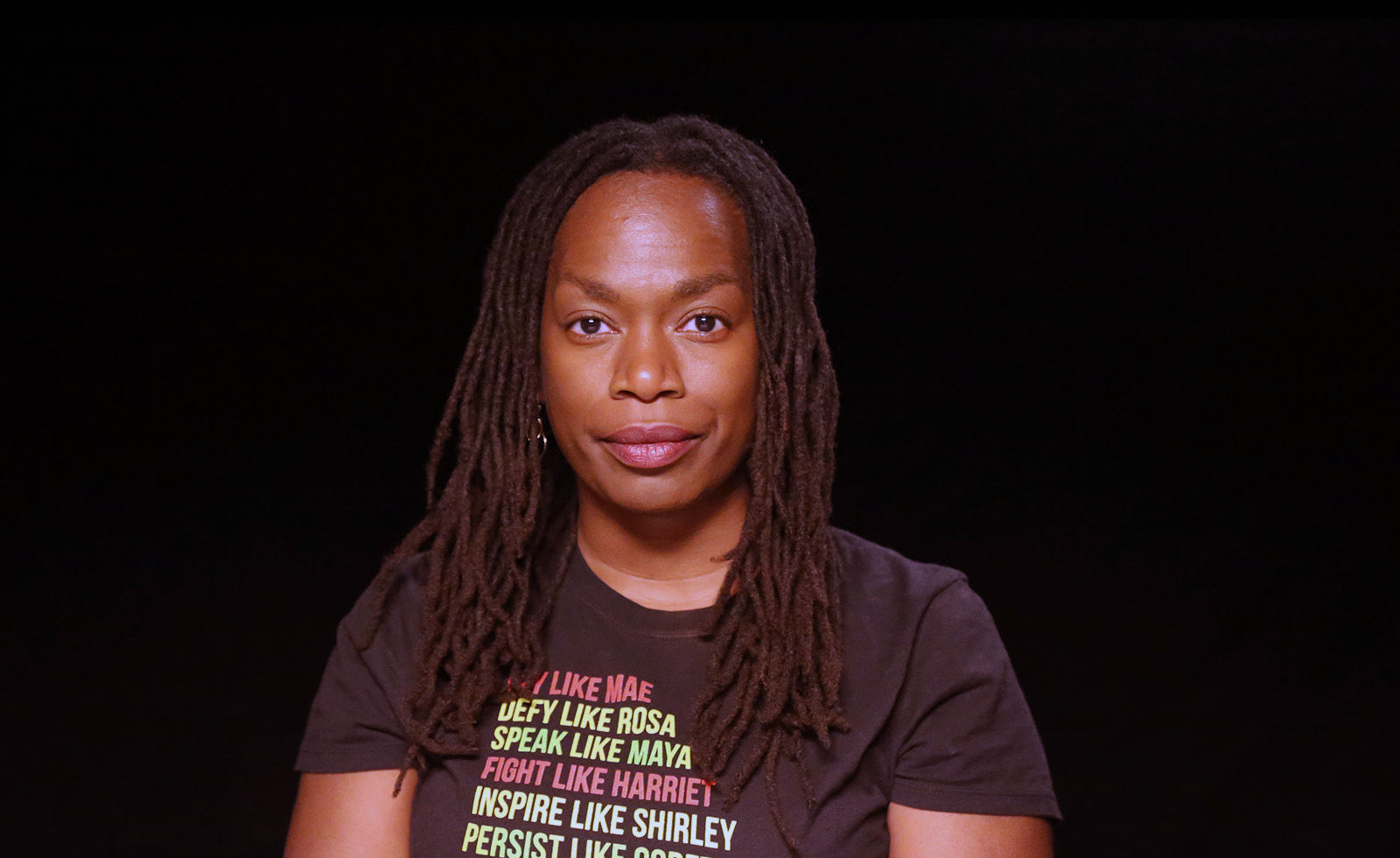

Nina Bernstein Michelle Daniel Jones

Michelle Daniel Jones Dr. Rita Charon

Dr. Rita Charon Kathleen Husler

Kathleen Husler Ateya Johnson

Ateya Johnson Rev. Wendy Calderon-Payne

Rev. Wendy Calderon-Payne Jasmine Bowie

Jasmine Bowie Shabnam Javdani

Shabnam Javdani Topeka Sam

Topeka Sam Alison Cornyn

Alison Cornyn